End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD), or kidney failure, afflicts more than 660,000 Americans a year and is growing at an annual rate of 5%.[1][2]While waiting for a transplant or living indefinitely without one, nearly half a million patients are on dialysis, an onerous treatment that siphons blood from the patient, filters it in an external machine, and then cycles it back into the patient’s body. Dialysis is an unpleasant, emotionally exhausting process, which typically involves three separate 4-hour visits to a clinic every week. At a government-negotiated price of $232.37 per treatment and a private-payor price of over $4,000 per treatment, it is also extremely costly.[3] Medicare spends nearly $35B per year on dialysis treatments alone, representing fully 7% of total Medicare expenditures.[4],[5]

The American dialysis industry hit an inflection point in 1972, when President Nixon signed a law that required Medicare to cover dialysis treatment for any American suffering from kidney failure, regardless of their insurance coverage. In the 1970s and 1980s the dialysis market consisted exclusively of small, privately-owned nephrology clinics. However, in the 1990s, two companies — DaVita and Fresenius — began packaging kidney drugs such as Venofer and Zemplar in unnecessarily large quantities, pushing doctors to overprescribe kidney medicine that was often thrown away, and thus overbill Medicare.[6]

Ultimately the government issued a warning to patients asking them to double-check prescription amounts with their physicians. A storm of negative PR forced DaVita and Fresenius to discontinue their fraud (DaVita later paid $450 million to settle a whistleblower lawsuit), and prescription quantities fell by a full 75%.[7] Bruised but not beaten or deterred, DaVita and Fresenius used their ill-gotten cashflow to launch a wave of consolidation, buying up many dialysis clinics in the country. Market dominance allowed the two giants to dictate the prices of inputs such as medical devices and buy out major manufacturers of dialysis machines.

In the 2000s DaVita and Fresenius embarked on a series of illegal schemes to boost their earnings including charging the government for unnecessary blood tests and paying kickbacks to physician groups for patient referrals.[8][9] Most recently, the duopoly used one of the largest nonprofit groups in the nation, the American Kidney Fund, to cover premiums for privately insured payers and encourage low-income patients to switch from government provided healthcare to private insurance.[10][11] Since private insurance is 17x as profitable as public reimbursement, analysts estimate that this scam was responsible for 30–45% of the giants’ annual pre-tax income.[12]

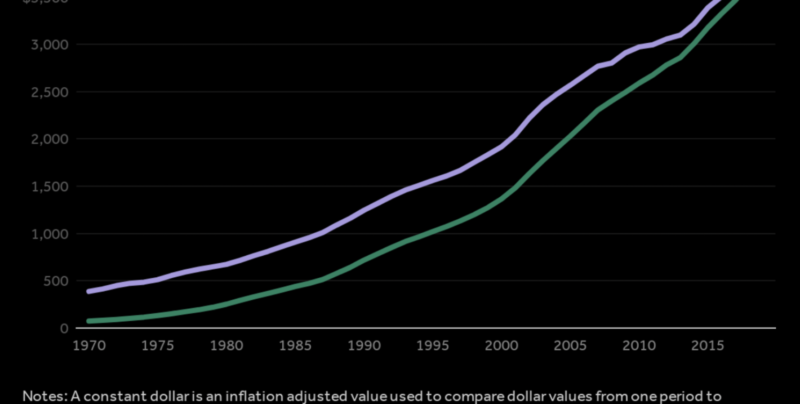

Today DaVita and Fresenius control 70% of the dialysis market, roughly 35% each.[13] DaVita has experienced truly explosive growth over the past two decades, climbing from a market cap of $724M to over $12.6B today.[14]Together, these corporations received $11.4B Medicare dollars last year, and did nearly $2B in after-tax profit.[15][16]

Of the remaining $22.6B paid out by Medicare last year, we estimate that roughly $5B went to DaVita and Fresenius’ smaller competitors, and the remaining $17.6B went to hospitals and other healthcare providers that typically own stakes in dialysis clinics and provide healthcare services.[17]The provider half of the market is extremely fragmented and regionalized, but DaVita and Fresenius’ unsavory maneuvers enable hospital and nephrology clinic partners to profit as well.

The cost of a broken dialysis industry is measured not merely in payor dollars but in human lives. DaVita and Fresenius have little incentive to introduce cheaper, more effective treatments, and consequently the United States has one of the highest kidney failure mortality rates of any industrialized country.[18] Mega-chain dialysis centers have far higher mortality rates than nonprofit dialysis centers — 19% higher at Fresenius facilities, and 24% higher at DaVita facilities, respectively.[19] Patients routinely complain about filthy dialysis facilities, and incompetent nursing staff. As many as 47% of dialysis patients are depressed or suicidal, which is orders of magnitude larger than CKD patients who are not on dialysis.[20][21]

America needs to drastically rework the incentives structure for CKD healthcare providers so that DaVita and Fresenius are encouraged to innovate and deliver cheaper services. We are optimistic about the introduction of “bundled payments” — capitated payments for complete treatment of a condition rather than for each individual service — which force dialysis clinics and drug manufacturers to internalize costs. To save money, providers are now using cheaper drugs such as Triferic (an iron booster) instead of Erythropoiesis Stimulating Agents (hormonal drugs which cause bone marrow to produce more red blood cells).[22] The jury is still out, but value-based care may decrease Medicare expenditures by incentivizing mega-chains to build holistic, preventative treatments around personalized medical data.

We need to fundamentally realign economic incentives so that CKD healthcare providers are rewarded for screening at-risk patients and intervening to prevent progression towards ESRD. Currently, the medical definition of “pre-dialysis screening” is any screening at least 3 months in advance of a dialysis treatment.[23] This is an absurd benchmark. Real preventative treatment such as weight loss, dietary changes, and the introduction of angiotensin-inhibitor medication must take place years in advance to make a difference. Today only 25% of patients have been followed by a nephrologist for at least a year before they reach end-stage disease.[24]

Universal coverage of dialysis treatment creates moral hazard by dis-incentivizing healthcare providers from attempting preventative treatments. Only by rewarding providers for prevention can we bring about real clinical change. One exciting model for preventative treatment is Medicare’s Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), which reimburses providers for lifestyle interventions that meet certain criteria (education, coaching, check-ins) and achieve weight loss in patients at risk for diabetes. DPP programs have achieved an average of 5% weight loss for participants, directly reducing their chance of developing diabetes and saving Medicare $2650 per patient per 15 months.[25] Reimbursements are available to traditional health care providers or more innovative programs on mobile health apps.

Finally, Medicare must revise policy so that providers treating chronic kidney disease are similarly incentivized to engage in real preventative care. In this mold, Kaiser Permanent conducted an experiment which assigned nephrologists to give physicians advice on how to test and advise Hawaiian patients with early-stage CKD. Kaiser’s experiment successfully reduced the number of patients who progressed to more advanced stages of the disease.[26]

Of course, preventative treatment isn’t a complete panacea. In the case that a patient progresses to ESRD and needs dialysis to stay alive, insurers and healthcare providers should encourage patients to pursue in-home dialysis over in-clinic dialysis at DaVita or Fresenius. Successful in-home dialysis requires that providers carefully teach patients how to self-administer treatment, a network of nurses to visit these patients, and tools for patients to report statistics on their blood composition. But in-home dialysis possesses many advantages over in-clinic dialysis: it is up to 5 times cheaper, is favored by most nephrologists, and is less stressful for patients.[27] In addition, haemodialysis nurses report higher job satisfaction and lower burnout rates in an in-home environment.[28] As you might expect, DaVita and Fresenius strongly discourage patients from pursuing this cheaper option.

We must shift market incentives so that payors and healthcare providers make money by experimenting with new strategies and technologies for treating chronic kidney disease rather than by allowing patients to accelerate to a government-covered terminal condition. Only a framework in which the best ideas win and spread through market forces — in which the market is aligned to lower costs and better outcomes with solutions such as value-based care — will ensure that Americans are able to secure the kidney care they need. In the case of chronic kidney disease, cheap, effective care is quite literally a matter of life and death.

Joe Lonsdale

Partner, 8VC

8VC is a San Francisco based venture capital firm investing in industry-transforming companies. For more information, or to sign up for our newsletter visit www.8vc.com

[1] “End Stage Renal Disease in the United States.” National Kidney Foundation, 2015.

[2] “Statistics” The Kidney Project, UCSF Department of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences. 2014.

[3] This is standard Medicare reimbursement; the figure is much higher for private insurers.

[4] https://www.usrds.org/2017/view/v2_09.aspx

[5] Brenoff, ibid.

[6] Pollack, Andrew. “Lawsuit Says Drugs Were Wasted to Buoy Profit.” New York Times, July 25, 2011.

[7] “DaVita to Pay $450 Million to Resolve Allegations That it Sought Reimbursement for Unnecessary Drug Wastage.” Department of Justice, June 24, 2015.

[8] Freudenheim, Milt. “Dialysis Provider to Pay $486 Million to Settle Charges.” New York Times, Jan. 20, 2000.

[9] Osher, Christopher. “DaVita to Pay $389 Million to Settle Anti-Kickback Investigations.” Denver Post, October 22, 2014.

[10] Thomas, Katie and Reed Abelson. “Kidney Fund Seen Insisting on Donations, Contrary to Government Deal.” The New York Times, December 25, 2016.

[11] Alpert, Bill. “Insurers Press Dialysis Claims.” Barrons, September 2, 2017.

[12] Rexaline, Shanthi. “American Kidney Fund Legal Issues A Major Overhang for DaVita Shares.” Benzinga, October 09, 2017.

[13] Neumann, Mark. “The Largest Dialysis Providers in 2017: More Jump on Integrated Care Bandwagon.” Nephrology News, July 17, 2017.

[14] Data from Ycharts.com

[15] See Fresenius Form 20-F for year ending in December 31, 2017, and DaVita 10-K for year ending in December 31, 2017.

[16] Shinkman, Ron. “The Big Business of Dialysis Care.” New England Journal of Medicine, June 9, 2016.

[17] Extrapolating from the fact that DaVita and Fresenius control only 70% of their market, the other 30% controlled by their smaller competitors would proportionally receive about $5B. Then, $34B minus $16.4B yields $17.6B.

[18] Fields, Robin. “God Help You. You’re On Dialysis.” The Atlantic with ProPublica, December 2010.

[19] Shinkman, ibid.

[20] Fields, ibid.

[21] Jong et al. “Prevalence of depression and suicidal ideation increases proportionally with renal function decline, beginning from early stages of chronic kidney disease.” Medicine, November 3, 2017.

[22] Charnow, Jody. “How ‘Bundling’ Changed Dialysis Care.” Renal and Urology News, March 2, 2017.

[23] Quaglia et al. “Early Nephrology Referral: How Early is Early Enough?” Archives of Internal Medicine, 2011.

[24] Lee et al. “Effects of proactive population-based nephrologist oversight on progression of chronic kidney disease: a retrospective control analysis.” BMC Health Services Research, 2012.

[25] Bresnick, Jennifer. “CMS Expands Promising Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program.” HealthIT Analytics, November 6, 2017.

[26] Lee et al. “Effects of proactive population-based nephrologist oversight on progression of chronic kidney disease: a retrospective control analysis.” BMC Health Services Research, 2012.

[27] McFarlane et al. “Cost savings of home nocturnal versus conventional in-center hemodialysis.” Kidney International, 2002.

[28] Hayes et al. “Work environment, job satisfaction, stress and burnout among haemodialysis nurses.” Journal of Nursing Management, 23.5, 2013.